Iran and Japan, two ancient civilizations separated by geography but united by deeply rooted cultural sensibilities, share more in common than is often assumed. From elaborate rituals of hospitality to a profound respect for tradition, both societies have developed social norms that prioritize propriety, humility, and continuity with the past. According to Japan’s ambassador to Iran, these shared civilizational traits shape not only everyday behavior but also the way the two nations interact on the international stage.

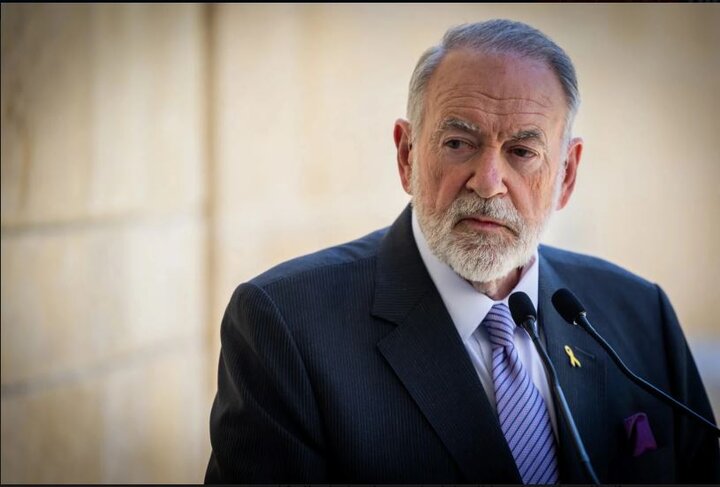

In order to elaborate the cultural commonalities between the two nations, Mehr News Agency conducted an in-depth interview with Tamaki Tsukada, Japan’s ambassador to Iran, focusing on shared civilizational values, cultural exchange, and the future of Iran–Japan relations.

Speaking about his experience in Iran, the ambassador highlighted similarities that resonate at a personal and societal level—from Iran’s ta’arof and guest-centered culture to Japan’s own etiquette-driven forms of respect. He noted that both countries have spent more than a century navigating the complex transition between tradition and modernity, grappling with the balance between East and West, history and change, peace and conflict. These parallel historical journeys, he argued, have profoundly influenced the lifestyles, values, and worldviews of both nations.

Here is the text of the interview:

Both Iran and Japan are ancient civilizations. In your view, what are the most important and prominent cultural commonalities between the two countries? How do you assess the future of cultural relations between Iran and Japan?

Well, I’m very glad that you asked that question, because I have always been thinking about that aspect of commonality between our two cultures as the Japanese ambassador to Iran. I think there are many levels and different angles from which we can observe and interpret the commonalities of our cultures and behavior.

At the personal level, for example, on a day-to-day basis, people greet each other with propriety. There is a very important ritual and style that people follow to show respect and humility to elderly people or to guests. In your case, you have Tarof or “Mehman Navazi.” We also have a similar way of greeting and receiving guests from abroad—hospitality. I am not a cultural anthropologist, so I do not go into this area too much. But as a diplomat, I have always thought about the way countries interact with other countries, rooted in those civilizational cultural traits.

Both Japan and Iran have experienced, in the past 150 to 100 years, a very difficult transition from tradition to modernity, the struggle between East and West, and how we reconcile our history with the reality that we face—peace and war. That has been a recurrent theme for both Iran and Japan: the question of East and West, tradition and modernity. So that, I think, forms the basis of our style of life and our way of behavior. When we talk about tradition, you celebrate Noruz or you have Shab-e Yalda. We also have similar practices.

So ritual, tradition, behavior—these are very important: propriety and manners. That is what I have been thinking about throughout my days here.

In recent years, Iranian youth have shown increasing interest in Japanese anime and the Japanese language. How do you evaluate this trend, and what plans do you have to further strengthen it?

First of all, as the representative of the Japanese government, I am very privileged to serve in a country that has such positive sentiment toward our country. I take it as my duty to further promote and elevate this very warm, positive sentiment that exists between Iran and Japan—especially in Iran. So we welcome and encourage this trend, and as the embassy, we want to serve as a facilitator, not an agent to impose anything. Because culture is not something that governments can enforce; it is more spontaneous. Otherwise, people will interpret it as propaganda, right?

And of course, that would be counterproductive. The recent feature is that pop culture represented by Japanese anime is very widely appreciated—not just in Iran; it’s a global phenomenon. So we would like to support it for what it’s worth through our embassy’s cultural activities, such as hosting film events, anime film events, or collaborating with Iranian artists and influencers. We would also like to promote young art students or design aspirants to consider studying in Japan. We have an open-door policy for international students to come to Japan. We have a number of very prominent art and design schools specializing in anime and cinematography. So these are areas which we would like to further publicize and invite young Iranian aspirants.

How would you describe the status of the Persian language and Iranian culture in Japan? To what extent are the Japanese people familiar with Iran’s history and cultural heritage?

Well, first of all, regarding Farsi—the Persian language—there are a number of very important higher education institutions in Japan, national universities. One is the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies; there is a faculty for Farsi, Persian language. Another is the University of Osaka, the Faculty of Language. Again, there is a Persian language course there.

In fact, there are a number of diplomats in our embassy currently who are graduates of either of these very distinguished universities, specializing in Farsi. And of course, other than these national universities, there are other private schools which teach or study this very old and important civilization, including the language. Many of the Farsi learners or Farsi researchers enter into this world through their interest in the olden times of Iran—not modern, contemporary Iran, but I would say the ancient Iranian civilization. So they tend to be more of a scholarly nature rather than learning the language for practical purposes.

But still, I think there is a very great level of admiration and respect for that great civilization. So that is the entry point. And another group, of course, is diplomats. They use the Farsi language as their skill to practice diplomacy and foreign policy. So these two are the main groups of Farsi speakers and learners in Japan. But I hope that there will be more general interest in this language. It is a very difficult language, I must admit. I am also taking lessons every week, but given my age, the progress is very slow. But I have great admiration and interest in this ancient language, and I would love to have more people enjoy this very, very fascinating experience.

To what extent is it possible to organize an annual Iran–Japan Cultural Week as a recurring event?

Well, actually, just a few days ago, we concluded this year’s cultural week. This year we featured Japanese film, contemporary cinema. Last year, we had a theme of Iranian artists creating or practicing Japanese culture. So we invited an Iranian origami artist, an Iranian ikebana artist, and similar genres of practitioners. Every year we have a specific theme dedicated to a specific area. This year we featured Japanese contemporary film.

Although it is a rather limited, short span of time, this has been a recurring event for at least the past 17 years. Maybe we were not capable enough to publicize this to a wider audience. But every year, we have a very good turnout of Iranians—from young to old, from all walks of life. And specifically in 2019, we marked the 90th anniversary of Japan–Iran diplomatic relations, and there was a big cultural event at that time. It lasted almost a month.

And by the same token, in Japan, almost every year. I can just cite a few examples. Last autumn, 2024 autumn, we had what we call the Eternal Persia exhibition, which exhibited art and arts and crafts and other interesting Iranian items from the Sasanid period onwards. In 2011, there was a similar art exhibition in Japan titled Glory of Persia. Its main feature was the Silk Road—mainly paintings, potteries, and porcelains which were traded between Japan and Iran through the Silk Road.

In 2006, this was one of the biggest exhibitions ever held in Japan on the theme of Iran, which was called the Grand Persia Civilization exhibition. In this exhibition, more than 200 items were actually transported from the Iranian National Gallery to Japan, and it was exhibited across Japan, throughout the country, for almost a year. So these are only a few examples of the impact which Iranian culture or civilization has had in Japan.

So, in the same vein, we would like to do a big, big cultural event to mark the centenary—the 100th year of diplomatic relations—which will come in three years’ time, three, three and a half years’ time: 2029.

What was the first Iranian dish you tried, and which Iranian food do you enjoy the most?

So one of the first Iranian dishes which I ordered in a restaurant—since I am a great lover of eggplant—was a stew, eggplant stew, Khoresh-e Bademjan, and also a dip, Kashk-e Bademjan. These were just exquisite—very, very tasty and delicious. And a few months ago, when I visited the town of Zanjan, I visited a street restaurant where they offered Jâgour Bâgour.

This was also a delicacy.

I did not imagine that sheep kidneys and livers tasted so, so awesome. But of course, this is not something that you want to eat every day. So from time to time, I long for this demonic great dish, Jâgour Bâgour.

Which place in Iran surprised or impressed you the most, and which cities do you personally prefer?

Well, there are maybe two categories of interest or attraction.

One is the element of surprise. The most sort of surprising experience when I came to Iran was my first encounter with Tehran. Because until then, I had never been to Iran until I first stepped into this country.

I had the expectation that Iran is a very traditional and very kind of suppressed or melancholic landscape. But after a few minutes drive in the town, it was totally an opposite experience.

It looked very kind of secular even European flavor and the sort of bustling and the energy and the economic activity, even the luxury.

This was not something that I was expecting. So that in terms of surprise, Tehran was the biggest surprise. In terms of the most inspiring or astonishing experience, I think by far Isfahan is my biggest sort of moment when I my eyes really were wide open. Of course the grandeur of the city the whole architecture, the planning of the city, andthe magnificence is out of the world. but at the same time I was really impressed by the very the subtle nature of all the angles and all the very minutia of the structures. you know the angle from which the sunlight comes in to make a specific shape of the shadow and all that is all calculated. It’s kind of symmetrical and mathematical which really was impressive.

So, I would say Tehran on the one hand and Isfahan on the other side. These are the two diametrically different experience but still has a great impression on me.

What is the most memorable or interesting experience you have had during your time in Iran?

Well, there are so many that it’s difficult to just say this was the most memorable.

but I would if you would allow, I have two very memorable experiences. One is my visit to the Japanese or the foreign cemetery in Ray, southern part of Tehran where there is a very small section dedicated to Japanese nationals who died in in in Iran or in Tehran. There are eight graves, tombs of Japanese deceased in Tehran. Most of them are very young.

Almost 100 years ago.

Which included even a two-year-old girl who was a daughter of a doctor attached to the Japanese delegation at the Japanese embassy in the 1930s. There is also a tomb dedicated to a young man. he his age was if I remember correctly 19 or 20, very young, a university student.

He was a son of a Japanese diplomat who worked in Tehran in those days. It was in the 1930s and he died of typhos. His mother was a Romanian actually. So his father was a Japanese diplomat and he was studying in Bucharest at that time in Romania and he visited his parents in Tehran and he died in Tehran because of the typhos. So just walking around the cemetery, I was able to feel the history and ponder about the various different lives of Japanese who lived in Tehran in those years. And another very memorable experience is this year during the 12-day war, at that time and I was spending my holiday in in Japan. But the war broke out and my boss ordered me to go back to Iran. So on the fourth day, I came back to Tehran via Azerbaijan. From Baku to Astara and along the Caspian Sea, we drove. From Qazvin to Tehran, it took about 10, 12 hours the drive.

But it was a very interesting experience because everybody was moving outside. But I was a very few people who were going reverse backwards. So we had the luxury of you know free auto lane, no cars. So it was very smooth and comfortable.

DID